“One thing I’ve always heard on the right is ‘Oh, a Great Awakening is gonna save us. You know we don’t need to do anything. God will come down and save us.’ We may have a Great Awakening but there’s no guarantee that the religion that will be awoken will be a reasonable one or an orthodox one. If anything you could argue we are in the midst of a Great Awakening right now and it’s the Great Awokening. It’s this secularized fanatical identitarian religion that preserves the Christian categories of original sin and inherited guilt but removes the possibility of redemption.” — David Azerrad, introducing a Ross Douthat talk.

Category Archives: Politics

Stranger in the known

Leafy says that welcoming the stranger includes welcoming the stranger in people we know well.

In search of liberalism

What I have been looking for is a vision of liberalism that justifies personhood (individuality) as our best access to God, because 1) it is only as a person that we encounter God as God, 2) it is only in interaction with fellow persons willing to accept and share personal uniqueness that we encounter God in others, and 3) it is through authentically personal and interpersonal encounters with reality in its myriadfold being that humankind cultivates living, sustaining communities.

Such person-founded communities help people 1) intuitively and spontaneously feel the value of life because the value of life flows into it from what surrounds and exceeds it, 2) to act effectively to create, preserve, repair and strengthen the necessary conditions for community in which personhood flourishes and 3) to share, preserve and honor these understanding through clear, demonstrable and inspiring accounts of truth, but truth that is sharply aware that it is only a part of reality, a mediating surface — a person-reality interface — not a container for reality, and certainly not a substitute.

Truth is especially not a container or substitute for any person. This is the crux of liberalism.

Where we try to substitute truth for reality and most of all the reality of others, we suffer the fate of King Midas. Everything and everyone we touch turns to cold, hard truth, and the world becomes a lonely, pointless and oppressive place.

“Transgressive realism”

Reading the introduction of Jean Wahl’s Human Existence and Transcendence, I came across this:

With this critique, Jean Wahl, at least I would argue, anticipates an important dimension of contemporary Continental thought, which has recently been quite daringly called by an anglo- saxon observer, “transgressive realism”: that our contact with reality at its most real dissolves our preconceived categories and gives itself on its own terms, that truth as novelty is not only possible, though understood as such only ex post facto, but is in fact the most valuable and even paradigmatic kind of truth, defining our human experience. The fundamental realities determinative of human experience and hence philosophical questioning — the face of the other, the idol, the icon, the flesh, the event… and also divine revelation, freedom, life, love, evil, and so forth — exceed the horizon of transcending- immanence and give more than what it, on its own terms, allows, thereby exposing that its own conditions are not found in itself and opening from there onto more essential terrain.

“Transgressive realism” jumped out at me as the perfect term for a crucially important idea that I’ve never seen named. I followed the footnote to the paper, Lee Braver’s “A brief history of continental realism” and hit pay dirt. Returning to Wahl, I find myself reading through Braver’s framework, which, of course, is a sign of a well-designed concept.

Braver presents three views of realism, 1) Active Subject (knowledge is made out out of our own human subjective structures, and attempting to purge knowledge of these subjective forms is impossible), 2) Objective Idealism (reality is radically knowable, through a historical process by which reality’s true inner-nature is incorporated into understanding), and 3) Transgressive Realism, which Braver describes as “a middle path between realism and anti-realism which tries to combine their strengths while avoiding their weaknesses. Kierkegaard created the position by merging Hegel’s insistence that we must have some kind of contact with anything we can call real (thus rejecting noumena), with Kant’s belief that reality fundamentally exceeds our understanding; human reason should not be the criterion of the real. The result is the idea that our most vivid encounters with reality come in experiences that shatter our categories…”

Not only is there an outside, as Hegel denies, but we can encounter it, as Kant denies; these encounters are in fact far more important than what we can come up with on our own. The most important ideas are those that genuinely surprise us, not in the superficial sense of discovering which one out of a determinate set of options is correct, as the Kantian model allows, but by violating our most fundamental beliefs and rupturing our basic categories.

This concept is fundamental to my own professional life (studying people in order to re-understand them and the worlds they inhabit, in order induce innovations through perspective shift), to my political ideal (liberalism, the conviction that all people should be treated as real beings and not instances of other people’s categories, because each person packs the potential to disrupt the very categories we use to think them) and my deepest religious convictions (the most reliable door to God is through the surprising things other people can show you and teach you, which can shock and transfigure us and our worlds.)

Though I am Jewish — no, because I am Jewish — I will never stop admiring Jesus for combining into a single commandment the Ve’ahavta (“and you will love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul and with all your strength”) with the imperative to love your neighbor as yourself. Incredible!

Transcendence, love and offense

Transcendence is what gives all things authentic value, positive and negative.

Positively, when we value anything, and especially when we love someone, what we authentically value is precisely the reality beyond the “given”, that is, beyond what we think and what we immediately experience.

If we only love the idea of someone or if we only love the experience of being with someone, while rejecting whatever of them (or more accurately “whoever of them”) defies our will, surprises our comprehension, breaks our categorical schemas and evades our experience, we value only what is immanent to our selves: an inner refraction of self that has little to do with the real entity valued. To authentically value , to love, we must must want most of all precisely what is defiant, surprising, perplexing and hidden.

To want only what we can hope to possess is to lust; to be content with what we have is to merely like, and no amount or intensity of lusting or liking adds up to love. (To put it in Newspeak, love is not double-plus-like. Love is not the extreme point on the liking continuum, but something qualitatively and, in truth, infinitely different.)

Conversely, authentic negative value — authentic offense — is our natural and spontaneous response when another person interacts with us as if we are essentially no more than what we are to them. They reduce us without remainder to what they believe us to be, and to how they experience us. In doing this, they deny our transcendent reality. This is the universal essence of offense.

When a social order is roughly equal, it is difficult, if not impossible, for one person to oppress another with such treatment. A person can either shun the would-be oppressor, or make their reality felt by speaking out or refusing to comply with expectations. But in conditions of inequality, threat or dependence can compel a person to perform the part of the self a more powerful person imagines. This is where offense gives over to warranted hostility.

The fashionable conventional wisdom, which has been drilled into the heads of the young, gets it all backwards. Ask the average casually passionate progressivist what is wrong with racism or sexism you’ll get an answer to the effect of “racism and sexism produce or reinforce inequality and oppression.” But the truth of the matter is that inequality is bad because it allows people to get away with forcing other people to tolerate, if not actively self-suppress, self-deny and perform the role the powerful demand of them. And part of that performance is asserting the truth the powerful impose.

Ambiliberalism report, late 2019

This weekend I hit a political breaking point. While my political position is as liberal as ever, and in better times would be considered left-of-center, Progressivism has become so dominant in left-wing politics and as a whole has drifted so far from liberalism I have realized it no longer makes sense to emphasize my points of agreement with it. I am now entirely and openly opposed to it, not only to its methods and rhetoric, but to its ideal.

Progressivism presents itself as anti-racist, anti-sexist, anti-prejudice, but does so by redefining racism, sexism and “bad” prejudice as bad only when deployed from positions of power. This means that if you claim to speak on behalf of a less powerful identity you can indulge your hatred toward (allegedly) more powerful categories of people without the risk of being called a racist, a sexist, or a bigot and whatever hateful language you use or vicious sentiments you express cannot be called hate speech, because you are “punching up” from a position of relative weakness.

And because Progressivists have a monopoly on determining what identities are politically relevant and which are not, Progressivism is protected from being itself understood as an identity — much less an overwhelmingly powerful identity. In many social milieus, including corporate workplaces, Progressivism is by far the most powerful ideology, both capable and eager to “punch down” with crushing force from positions of authority.

Progressivists have a collective habit of scoffing at such claims and reacting in the manner that all overwhelmingly powerful groups do when confronted with their own prejudice (with dismissal, fragility, offense, rage, etc.). They appear to lack the ironic and emotional self-discipline to recognize when they themselves are facing truths outside their own comfort zones and to respond with the empathy and openness they demand from others.

So, I’m not even sure what the practical consequence this shift will have besides refusing to stress points of agreement when speaking with Progressivists, and not pleading with them to see me as a fellow left-liberal. They’re not liberals, and I’m not all that sure most of them know what left means, either. I’m definitely not going to cooperate with racist, sexist, bigoted and hate-saturated redefinitions of racism, sexism, bigotry and hate speech. They need to be called out, however unpopular they are and however much racists and sexists and bigots resent being told the truth.

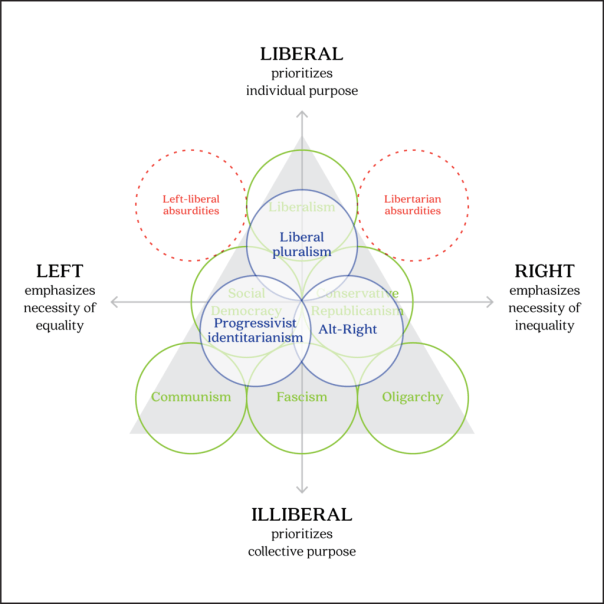

I’ve also redrawn my Ambiliberal diagram to situate my own Liberal Pluralism against Progressivist identitarianism and its antithetical twin, the Alt-Right.

Design supremacist rant

If you think about your work output as objective, tangible things, design can look like a wasteful delay to productivity.

But if you think about your work output in terms of improvement to people’s lives, churning out things as fast as possible, without concern for their human impact might be productive — but most of the productivity is production of waste.

This is why, once the world overcomes the industrialist worldview that confuses objectivity with the ruthless disregard for subjectivity (and essentially imposes a sort of institutional asperger’s) and we realize that the world as we know it and care about it (including all our objective knowledge) is intertersubjectivity woven, empathic disciplines will be more fairly compensated. Then we will stop wringing our hands over why so few women are attracted to STEM and begin applauding them for having the good sense to concern themselves with ensuring our efforts are focused on the well-being of humankind. And when this happens, don’t be surprised to see VPs of IT reporting up to Chief Design Officers who gently insist that they hold their horses and think about human impacts before spastically building as much stuff as they can as fast as they can. The world needs people like that, but they need supervision from people who can put all that building in purposeful context.

Civilizational mystery

This passage from Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty offers insights valuable to two of my favorite subjects, 1) design, and 2) postaxial conceptions of religion:

“The Socratic maxim that the recognition of our ignorance is the beginning of wisdom has profound significance for our understanding of society. The first requisite for this is that we become aware of men’s necessary ignorance of much that helps him to achieve his aims. Most of the advantages of social life, especially in its more advanced forms which we call ‘civilization,’ rest on the fact that the individual benefits from more knowledge than he is aware of. It might be said that civilization begins when the individual in the pursuit of his ends can make use of more knowledge than he has himself acquired and when he can transcend the boundaries of his ignorance by profiting from knowledge he does not himself possess.”

If civilization begins and progresses by allowing individuals to benefit from more knowledge than we are aware of, design advances civilization by both harnessing and hiding knowledge (in the form of technologies) beneath carefully crafted interfaces, disencumbering users to advance their own specialized knowledge, which in turn can be harnessed and hidden.

And of course, the mention of “transcending boundaries of ignorance” connects directly with my preferred definition of religion as the praxis of finite beings living in the fullest possible relationship with infinitude. My own religious practice involves awareness of how transcendence-saturated everyday life is, especially toward the peculiarly inaccessible understandings of my fellow humans. But study of Actor-Network Theory and Postphenomenology has increased my awareness of how much non-human mediators and actors shape my life. The world as I experience it is only the smallest, dimmest and frothiest fuzz of being entangled within a dense plurality of worlds which overlap, interact and extend unfathomably beyond the speck of reality which has been entrusted to me. Civilization involves us, but exceeds us, and is far stranger than known.

By the way, I still intend to read Jaspers’s and reread Voegelin’s writings on the Axial/Ecumenic Age to better understand the societal forces which produced the recent and idiosyncratic form of religiosity so many of us mistake for eternal and universal. And I’ll read it from the angle that if it has changed before, it can change again. I think human centered design offers important clues for how it can change.

Propaganda

Propaganda is popular news, in the same sense that romance novels and action films are popular art. By “popular” I mean they function comfortably within the worldview of the masses, and serve to reinforce commonly held beliefs, values, practices, assumptions, blindnesses and taboos.

We don’t realize it yet, but a lot of what today’s smart people think is serious literature is a combination of propaganda and popular art, basically popular fables, complete with a tidy moral at the end.

Protected: Resolutions related to value

Reasons to love design research

Some people love design research for purely functional reasons: it helps designers do a much better job. Others just love the process itself, finding the conversations intrinsically pleasant and interesting.

These reasons matter to me, too, to some extent, but they never quite leave the range of liking and cross over into loving.

Here are my three main reasons for loving design research, listed in the order in which I experienced them:

- Design research makes business more liberal-democratic. — Instead of asking who has deeper knowledge, superior judgment or more brilliant ingenuity (and therefore is entitled to make the decisions), members of the team propose possibilities and argue on the basis of directly observed empirically-grounded truths, why those possibilities deserve to be taken seriously, then submit the ideas to testing, where they succeed or fail based on their own merit. This change from ad hominem judgment to scientific method judgment means that everyone looks together at a common problem and collaborates on solving it, and this palpably transforms team culture in the best way. This reminds me of a beautiful quote of Saint-Exuperie: “Love does not consist in gazing at each other, but in looking outward together in the same direction.”

- Design research reliably produces philosophical problems. — Of all the definitions of philosophy I have seen, my favorite is Ludwig Wittgenstein’s “A philosophical problem has the form: ‘I don’t know my way about.'” When we invite our informants to teach us about their experiences and how they interpret them (which is what generative research ought to be) we are often unprepared for what we learn, and often teams must struggle to make clear, cohesive and shared sense of what we have been taught. The struggle is not just a matter of pouring forth effort, or of following the method extra-rigorously, or of being harmonious and considerate — in fact, all these moves work against resolution of what, in fact, is a philosophical perplexity, where the team must grope for the means to make sense of what was really learned. It is a harrowing process, and teams nearly always experience angst and conflict, but moving through this limbo state and crossing over to a new clarity is transformative for every individual courageous, trusting, flexible and benevolent enough to undertake it. It is a genuine hero’s journey. The opportunity to embark on a hero’s journey multiple times a year is a privilege.

- Design research is an act of kindness. — In normal life, “being a good listener” is an act of generosity. If we are honest with ourselves, in our hearts we know that when we force ourselves to listen, the talker is the true beneficiary. But paradoxically, this makes us shitty listeners. We are not listening with urgency, and it is really the urgent interest, the living curiosity, that makes us feel heard. Even when we hire a therapist, it is clear who the real beneficiary is: the one who writes the check for services rendered. But in design research, we give a person significant sums of money to teach us something we desperately want to understand. We hang on their words, and then we pay them. People love it, and it feels amazing to be a part of making someone feel that way. In a Unitarian Church on the edge of Central Park in Manhattan there is a huge mosaic of Jesus washing someone’s feet, and this is the image that comes to mind when I see the face of an informant who needed to be heard. (By the way, if anyone knows how to get a photo of this mosaic, I’ve looked for it for years and have never found it.)

Glossary of unattainable ideals

Sunday morning I was talking with Zoe about different varieties of unattainable ideals, and further developing a distinction I made last week, when I criticized altruism for belonging to a misconception of being and relationship that produces ineffective practices and bad results, contrasting it with “impossible” ideals which can never be fully actualized but which are valuable, nonetheless.

Here’s the start of a glossary of unattainable ideals:

Sacred mirage: an impossible end is justified by intrinsically valuable means — so even though the goal is unattainable on principle (that is, progress even toward it is absurd) the effect of pursuing the ideal is intrinsically good.

Asymptotic ideal: an end can never be fully attained, but steady progress toward that end is possible — so the act of pursuing the ideal can be expected to produce value even if perfection is never reached. Rorty’s concept of progress as measured by movement away from a negative ideal is helpful in cases of asymptotic ideal.

Futile ideal: an unattainable end fails to justify means whose value is purely utilitarian — because the value of the means is contingent on attainment of an unattainable goal the act of pursuing the goal is a waste of time and effort.

Corrupt ideal: a misconceived end produces intrinsically harmful means — so, not only is the end impossible, the means employed to obtain it are damaging. A corrupt ideal is an inversion of a sacred mirage, a “desecrating mirage”.

*

I regard altruism in its myriad forms as a corrupt ideal. It does not produce relationship with real others, but intense feelings toward categories of person who exist primarily in the imagination of the altruist.

I see the illiberal fringes of progressivism as rejecting liberal democracy as a futile ideal, when, in fact, it is an asymptotic ideal, and desiring to replace it with a corrupt ideal, which ultimately undermines their leftism and enthrones them as the elite arbiters of justice according to their own corrupt ideal. The “illiberal left” is not leftist at all, but rather an alt-alt-right who wants to abandon the principles of both liberalism and democracy in order to administer its own moral vision on a majority who does not share their vision (even if they prefer it as a lesser evil to right-illiberalism).

The illiberal fringes of the right also subscribe to a corrupt ideal, antithetical to the left, but antagonistically cooperative with it. I call these antithetical pairings “Ares’s hand-puppets” because they are animated by the same kind of collective hubris that justifies the indignation and retaliation of the other. The illiberal right also pursues an ideal entirely incompatible with liberal democracy, based on scientistic convictions that have nothing to do with science, and which are unacceptable to the majority (even if they prefer it to progressivist-illiberalism).

Liberal democracy, as I said, is an asymptotic ideal, but it also has virtues of a sacred mirage, that is, liberal-democratic practice has life-enhancing virtues apart from the progress it effects, and the more I contemplate it, the more the intrinsic value of the ideal appears to surpass its contingent value. The intrinsic value might even serve as the source of the continent value, in that progress toward the liberal democratic ideal means that increasing numbers of people benefit from the intrinsic value of pursuing the liberal-democratic ideal.

*

Now that I’ve applied these concepts (informally prototype tested them), I’m seeing opportunities for refinement by categorizing unattainable ideals as having three dimensions:

- Practicability (practicable / impracticable): is it possible to progress toward the ideal’s goal?

- Intrinsicality (intrinsic / contingent): How much intrinsic value do the means have?

- Morality (positive / negative): What is the intrinsic value of the means?

Respect: experiences, versus interpretations of experiences, versus…

I listen to other people speak of their experiences, and I also listen to their explanations of their experiences. The former is privileged knowledge: respect entails belief in the other’s testimony. The latter is not: our explanations for the experience belong to our own theories founded in our own philosophies. And here respect entails allowing each individual to hold their own beliefs on what caused the private experience.

Perhaps these two respects deserve different names.

*

If you experience God speaking directly into your ear, I must respect your testimony or risk disrespecting you — but you must respect my interpretation of your testimony or risk disrespecting me.

*

If my child throws a fit, I must believe she is experiencing real distress or I am failing as a parent — but I must interpret that distress and respond to it as an adult parent or I am failing in a different, perhaps worse way — a way that neglects the obligation of parents to teach their children to interpret their own emotions and to respond to them in a socially reasonable way.

*

What should these differing forms of respect be called?

- The respecting of direct testimony of experience, taken on faith as true.

- The respecting of interpretation of experience, taken as one of a plurality of arguable truths.

There is a third respect I have not mentioned, one in which I might be deficient. This is respect for rigorous comparison of experiences (at least empirical, sharable experiences) and interpretations (at least interpretations that are strictly logical) and their consequences, which means abandoning one’s favored interpretations when another is shown to have more explanatory power. This would probably be called scientific respect. Or… (see below) positivistic respect…?

But, then, there is the respect for precisely those experiences that are least sharable and conclusions that are reasonable but not determined by any logic fed by empirical data, one that recognizes that relevance is a function of framing and that reality infinitely exceeds our perception, conception, comprehension and understanding, and when reality is beyond not only our grasp but even our our touch, it is indistinguishable from nothingness — not that dark nothingness that announces its present absence with a shadow, but that absent absence, the blind nothing that looks like the expected somethings, the reality that can stare directly into each of our pupils and breathe the air directly from our nostrils, unperceived, undetected, unsuspected.

Some assertions are experiential, some interpretive, some positivistic, and these deserve their own kind of respect, but some assertions are none of these and aim at what is beneath and beyond all of them together — and this commands an enforceable philosophical respect. Or is it religious respect?

Bourgeois Marxism

I wonder what it would look like if the bourgeoisie appropriated Marxism, and then deployed it against the working class.

Solid-gold inspiration

Anxiety is an unpleasant type of inspiration.

*

Despising anxiety is not only a waste of inspiration, it is alienating.

*

The Golden Rule is not gold-plate — it is solid gold all the way down, and nobody finds the bottom. But a morally serious person follows the gold down as far as it goes, and further.

*

What does it mean to follow the Golden Rule deeper?

Starting at the surface: Do you want others to do do to you exactly what they want done to them? Would you like them to feed you only the food they want to eat themselves and make you listen to the music they would have played for them? Clearly this is not deep enough.

Further down: Would you like others to treat you justly, according to their own sense of justice, in disregard of what seems just, fair and good to you? Do you want them to privilege their own instincts and conceptions — their own conscience — which makes their justice seem as self-evident to them as yours is to you?

Do you want them to believe their anxious suspicions that you think and act in bad faith, and to do everything in their power to stop you and silence you if possible?

Clearly, we must mine deeper.

The more layers we dig beneath — and the more we undermine our own moral complacency by applying the Golden Rule as strictly to ourselves as we apply it to others — the more we discover not only changes in what we believe about morality, but we also change how we believe moral truths, and deeper still, why we care about morality.

*

When we make others anxious with our ideas, they are full of reasons why they ought to take their anxiety literally, give their paranoid suspicions full reign, and obey its logical consequences and shut us down in whatever way is most efficient.

And if we are willing to apply the Golden Rule symmetrically — as the Golden Rule implies we must — we find we do the same thing to others, all the time, constantly. We can find myriad reasons to silence others, if only in our own head, if only temporarily, if only through saying “maybe later…” It takes tremendous discipline and pain tolerance to do otherwise.

*

If we welcome anxiety as inspiration, interpreting what it says to us, letting it work on us, allowing it to be productive through us — everything changes.

Everything, literally.

*

Anxiety is how real transcendence feels before our understanding renders it immanent.

*

Anyone who wants religion to be an instrument for annihilating or banishing anxiety and having only peace — whether through outer-fight or through inner-flight — is looking for something other than religion.

Religion is for cultivating the fullest possible relationship with reality beyond our understanding. Religion is inherently anxious.

*

Liberalism is far deeper than authoritarians will allow themselves to know.

*

Maybe we need a Solid-Golden Rule: Apply the Golden Rule to yourself as you would have others apply it to themselves.

Two definitions of justice

For some, justice is primarily a matter of determining guilt and proper punishment. For others, justice is also a matter of determining innocence and proper protection.

*

I remember back in the mid-2000s, when I was caught up in the general leftist panic about the underlying philosophy of the Neocons and decided to dig into the substance of their thought for myself. The panic turned out to be justified. The passage below comes from Irving Kristol’s Neo-Conservatism: An Autobiography of an Idea:

The main priority of a sensible criminal-justice system — its first priority — is to punish the guilty. It is not to ensure that no innocent person is ever convicted. That is a second priority — important but second. Over these past two decades, our unwise elites — in the law schools, in the courts, in our legislatures — have got these priorities reversed. (Page 362, “The New Populism: Not to Worry”)

That is a pretty weird way to frame justice, but it rings eerily familiar is some conversations I’ve had with Progressivists lately. If you wanna make an omelette, you’ve gotta break some eggs.

I am not yet persuaded

People – especially empathic people – can sometimes forget that they, too, have a right to be persuaded.

They unconsciously assume the burden of persuasion, and feel that if they have not persuaded others to their belief, they do not have the right to their own beliefs, or at least not to public belief. They think that until they can argue a belief, they are obligated to keep it to themselves and suppress or conceal their doubts.

I think this can be harmful.

I consider it a liberal’s right, if not a duty, to express non-persuasion or even dissent when it exists, even when there is no strong argument to back up the belief. This practice is important for a number of reasons. If nobody disagrees or doubts, it creates an appearance of unanimity, suggesting self-evident truth. It can cause people to doubt their own doubts and worry that their questions are stupid or misguided. If this fear becomes widespread and habitual, and people stop raising questions and everyone becomes unaccustomed to unquestioning acceptance, a culture of conformity can develop where group-think is the rule and questioning is taboo.

Registering doubt at least keeps questions open. It also encourages other individuals with doubts to speak up. It keeps a society accustomed to hearing individual judgments and individual thinking that goes against the grain.

To a liberal these are concerns of the highest rank.

*

My conviction is that we can believe or not believe something even without strong arguments.

Of course, if we want people to agree with us, we’ll eventually have to produce some persuasive reasons. Until then it will be necessary to stand alone.

But we are allowed to stand alone. Some of us admire people for standing alone – as long as they also respect our right to be unpersuaded.

*

Advice to myself:

If I find myself in the midst of a group with whom I disagree, I will raise my hand and state: “I am not persuaded by what you are saying.”

I will openly admit it if I do not yet have counter-arguments. I will tell everyone I’m still thinking about it.

I will not be silent, and I definitely won’t be silenced.

Progressivists

As Christian fundamentalists who wish to forcibly impose their views on a population are called Christianists, and as Islamic fundamentalists who wish to forcibly impose their views on a population are called Islamists, Progressive fundamentalists who wish to forcibly impose their views on a population should be called Progressivists.

And why shouldn’t they? They have had powerful conversion experiences that revealed the true Truth to them. Now they see the world in its totality with an undeniable intensity, clarity and coherence. They know, they know that they know, and they no longer have patience for those who have no desire to know. They cannot conceive of how they could possibly be wrong, nobody is able to show them to their satisfaction how they are wrong, and therefore they are right.

Some are “born again”, some are “enlightened”, some are “red-pilled”, some are “woke”, and all are naive realists who think they awoke from naive realism, and they are going to wake you up, too.

Classy progressives

Conversations among progressives can be confusing.

When politics is the topic, everything seems very leftist. They regard exclusivity, privilege, elitism, inequality, unfairness and consumerism as abhorrent and are quick to call it out when they see it.

But when the talk turns to less weighty topics, egalitarianism goes out the window. It becomes a competition to see is most urbane, who has vacationed in the most exotic places, who has the best taste in wine, literature, cinema and art, who knows the most about the newest, most fashionable restaurants, who has a degree from the most prestigious university, who has what status in what airline, hotel and credit card. Who has the highest status?

It all seems very self-contradictory — unless you realize that political beliefs and social ethics is just another of these status qualifications.

To establish that one belongs to the progressive elite class one must have the best taste in food and drink, must vacation in the best places, must have the best educational pedigree and one must believe the right things and practice the best political etiquette most strictly.

Seen in this light virtue signaling is just another dimension of a larger class signaling.

Assuming a progressive elitist class exists, would progressive elitists be aware of the advantages they derive from their dominant identity? Would they be able to overcome the a form of motivated reasoning that sees unjust privilege everywhere but in its own identity? Wouldn’t they feel deeply uncomfortable when confronted by others, and perhaps feel some fragility and rage at having their dominance challenged and at the impudent demand that they share power with those who are different from them? Could they be quiet and really listen for a change, instead of lecturing and dominating the discourse? Could they accept the hard truth that, even with their deductions, counter-balances and privilege-checking they have refused to check the one privilege that dwarfs all the others combined?

Could they apply their own principles to themselves? Or will they use their power to dismiss, discredit, disgrace and punish attempts to speak truth to a power identity so powerful that it demands to be treated not as an identity but as truth and justice itself?

The “yes, but, so” of pseudoliberalism

What is it about Rorty that makes him so satisfying to disagree with? Rorty’s mistakes and omissions make me like him even more. Maybe it is because his ultimate goals and tacit evaluations correspond to my own, and our disagreements are merely around facts and inferences.

Rorty was profoundly pluralistic, and you can feel it.

[I meant to just write about Rorty, but here the post takes a turn toward the theme of emergencies and liberalism, which appears to be my live problem right now.]

Rorty, as far as I know, never did that pseudoliberal move of piously nodding to the ideal of liberalism and then immediately finding reasons to betray it for the sake of saving it from those illiberal others.

Yes, there are illiberals. Yes, they attack liberalism from the inside when they attack it from the outside by forcing it to resort to illiberal measures to defend itself. But with pseudoliberals the eagerness to find necessities to resort to illiberal measures is palpable. Their faces brighten when they find the “yes, but… so…” that lets them have it both ways: appealing to liberal principles to support their own liberty, while finding themselves in the midst of an emergency that calls for privileging their own judgments over those who view things differently. “Yes, but people’s safety is at risk, so…” “Yes, but there is corruption (or conspiracy!) at the very root of the institutions we are supposed to trust, so…” “Yes, but the public is too deluded and stupid to judge for itself, so…” “Yes, but the USA’s form of liberal democracy was corrupted from the start, and the stain of sin remains, so…” “Yes, but we are being overrun by hordes of illegal immigrants, so…” etc., etc., etc.

*

Saturday, I tried to explain to a conservative friend that if we arbitrarily decide an illegal immigration problem (that is actually on a trajectory of improvement) is such an emergency that it justifies use of extra-democratic emergency powers, he has no right to complain in 2022 when President Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez declares an emergency over poverty or institutional racism or worker’s rights.